I am quite fond of apocalyptic fiction, which are works that include the end of the world as a key element. There are lots of these, and they range in severity and details. In some ways, it is one of the classic topics of science fiction.

Robert Heinlein covered the topic in his novel, Farnham’s Freehold, which involves a family sent into an apocalyptic future during a nuclear war. The novel has a lot to say about race, and I don’t think those parts of it have aged very well, but it is interesting how the novel assumes a certain social structure in the survival shelter. The family patriarch assumes control over the family’s actions (and their Black servant) until the situation is reversed by their capture by a future Black-dominant civilization. In a lot of ways, Heinlein was satirizing the assumptions of the time, but those assumptions remain strong even to this day.

David Weber’s Out of the Dark has a similar, family-oriented (but less racialized) understanding of survival in an apocalyptic situation. The family that part of the story focuses on, the Dvorak family, is said by some critics to be based on Weber’s own, and the family is depicted as naturally falling into a hierarchy headed by David Dvorak, who owns the house they live in.

Larry Niven’s Lucifer’s Hammer has a similar structure, but instead of a family-run apocalypse survival community, the survival group he depicts in the wake of a comet striking the Earth is ruled by a combination of technocratic leadership (people who know how to build and operate high technology) and the pre-apocalyptic democratically elected leadership that has become increasingly feudal. Once again, things are exclusive and organized around family lines. Similar ideas to these can be found in Niven’s other novels, such as Fallen Angels where a small civilization of astronauts works to maintain its technology in the face of a hostile Luddite regime on Earth, or Oath of Fealty where an arcology in Los Angeles organically begins to develop a paternalistic, feudal character in the face of exterior urban decay.

Of course, all of these authors have particular views that inform their writing on the apocalypse, and that can be seen in their writing. Niven, Weber, and Heinlein are all at least vaguely right-of-center on some political issues and the apocalypse (and surviving it) tends to be an issue that has a sharp partisan divide.

Still, other visions of the apocalypse from writers with other viewpoints have similar outcomes. I recently read the dystopian post-apocalyptic novel The Office of Mercy where the last bastions of technological civilization in the world operate a campaign of genocide against less-technological (but not stupid or particularly primitive) outsiders. There, it is explicitly mentioned that the exclusive, genocidal civilization that the protagonists belong to used to be more open, and then closed itself off after the apocalypse, which is justified by in-story actors as necessary. The author doesn’t seem to agree with the viewpoints of the characters that were responsible for this change, but it is another case of a society becoming more insular in response to an apocalyptic disaster.

Hugh Howey’s Silo trilogy has a similar setup, with isolated fallout shelters being intentionally kept apart and ignorant of each others’ existence, forming authoritarian societies by design. Once again, there is the separation of people in the apocalypse.

More popular media has this assumption as well. In Waterworld, society is divided into small survivalist atolls, which are floating walled cities, that struggle with gang violence outside. In the 2006 TV show Jericho the titular city has to deal with hostile powers outside, and the more recent Fallout series of TV shows (and video games) has a bunch of small, embattled civilizations, with a few exceptions.

It seems natural, to us, that the apocalypse should lead to people being separated. Without the means to travel long distances, people will become organized on a more local level, and with a shortage of resources, it becomes impossible to help outsiders, and they might want to take some of the little that you have!

“Nonfiction” survivalist literature is built on just this premise. Ragnar Benson, the anonymous author of dozens of books on subjects such as improvised weapons, survivalism, and emergency medicine, makes it very clear in Ragnar’s Urban Survival that he believes that “no matter what, never, ever become a refugee… Refugees are totally the wards of the government.” You can find similar themes in other books from the Loompanics/Paladin crowd, like Concrete Jungle by Clay Martin, a more modern figure in the survivalist community.

And this distrust of outsiders and especially institutional authority does make a certain degree of sense. Since the decline of the hippie movement, survivalism as a concept has been heavily dominated by right-wing libertarian types. These are who you imagine when you hear “survivalist”—a middle aged, white man, with a backyard bunker full of canned food and a whole bunch of guns. There is also, however, some practical benefit to a more individualistic perspective.

In Kansas, a company known as “Survival Condo” is currently offering condominiums in a former missile silo. Similarly, companies like Vivos, Atlas Survival Shelters, and Rising S all offer backyard bunkers or rental options, and there are entire realty companies that specialize in selling disused bunkers and missile installations. These bunkers claim to be able to protect against a variety of threats: missile strikes, intruders, nuclear explosions, biological and chemical weapons, futuristic super-plagues. And, of course, the space inside is limited, making them a potentially valuable commodity. And many survival resources that someone might squirrel away are similarly limited: canned food, good toilet paper, guns and ammunition. If you can’t acquire more resources, it makes sense to hoard what you have, and guard it jealously, and you can only save so many people even if you did give freely. If you think that the state of crisis will last indefinitely, there’s no way to ration out what you have between an unknown number of people. You have to choose who is most important to you, and protect that at all costs. This leads to the organization into family structures that is often assumed.

This organization is also especially natural-feeling for the audience for much survivalist literature: middle-aged white men, usually with families. These people expect to be the patriarchs of their household and the paternalistic view of survivalism comes naturally to them. Furthermore, the ideas of hostile, post-apocalyptic raiders or remnant governments reflect social anxieties. Post-apocalyptic raiders are exaggerated versions of the hostility that people living in gated communities expect from the unwashed masses outside, and a remnant government often reflects how people see their own governments: ineffectual, corrupt, and oppressive. There are clearly deep ties to American conservatism and libertarianism.

But these systems are by no means the only ways that one can think about the apocalypse. It is often assumed that the cities will become places of mass death, and on the surface this makes perfect sense. Cities are in some ways the pinnacles of our civilization, supported by an enormous pyramidal supply chain that stretches around the globe. By comparison, a subsidence farmer may be relatively poor, but their supply chain seems to start and end in their own backyard.

Of course, in the modern age it is not so simple. Modern farming involves large, expensive, and technologically-sophisticated pieces of equipment, like tractors, harvesters, and irrigation machines. Many of these are designed to be difficult to repair in the field, and even if repairs are possible, they will not be possible indefinitely and many of these machines rely on supplies of things like gasoline, diesel, and lubricating oil. That is not to say that farmers and rural are more dependent on the outside world than urbanites. They are certainly more independent. But they are not totally independent, and would suffer as well in most apocalyptic scenarios.

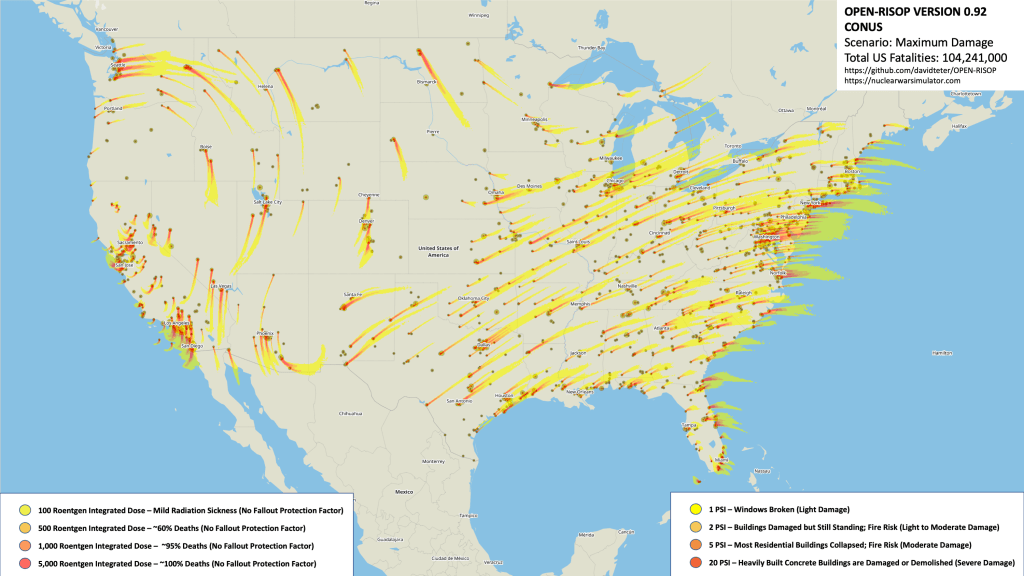

And the city-dwellers don’t have it as bad as things may immediately seem. Cities are obvious targets in a global thermonuclear war, especially in the current age of mutually assured destruction, but modern cities are likely to be somewhat resistant to nuclear blasts, with large buildings attenuating shockwaves and preventing the spread of fires from the extreme light and heat of the nuclear blast. Even for disasters where cities suffer more, like plagues, they have one advantage: there are more people there to suffer.

In crises, cities are generally the places that are most aggressively protected by governments. When Hurricane Katrina heavily damaged New Orleans, there was lots of media attention paid to the unrest and chaos in the city itself after the hurricane devastated the city, but it’s important to keep in mind that help did come in the form of the national guard and federal reconstruction aid. In the event of an apocalyptic crisis, assistance would likely be given first to cities. That’s where FEMA tents would be set up, where relief would be distributed, and where whatever law enforcement capability remained would start their work.

This can be seen in more ancient history as well. In apocalyptic crises like the breakup of the Roman Empire or the collapse of the Olmecs, many people die, including and especially in cities, but after the crisis subsides, the cities that were important to the preexisting empires continue to be important and form the nuclei of new civilizations, such as the kingdoms of the “barbarian” Theodoric on the Italian peninsula or the later Aztecs being established around three powerful cities that were once ruled by the Olmecs. During the black death, many of the cities of Europe had streets full of the dead—and yet Rome, Paris, and London remained great and important cities which were continuously inhabited through disasters.

Cities retain their populations, which remain valuable, and even in the modern day the infamously deindustrialized cities of America still contain millions of artisans, engineers, doctors, scientists, and other people who would be valuable to a re-emerging civilization, and factory hardware is often not extremely far from cities for the simple reason that those factories are operated by people who live in cities.

Coming back to the depiction of the apocalypse in science fiction, a city-first and top-down model of reorganization after a societal collapse can be seen in a few works. Stephen King’s The Stand involves society collapsing due to the accidental release of a deadly bioweapon, and in the wake of the disaster the survivors end up converging on the cities of Boulder and Las Vegas, establishing civilizations by pooling their resources in the cities after the mass dying.

In A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr., civilization after a nuclear war remains located in major cities—Texarkana becomes the capital of a major empire and St. Louis becomes the capital of a North American papacy when the connection to Rome is lost. In the similar novel Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd Century America, the cities of the United States remain largely intact, and New York is the capital of a degenerated United States after a peak-oil civilization collapse. Fitzpatrick’s War by Theodore Judson has a similar situation, with the Yukon Confederacy (an intercontinental anglophone empire loosely related to the US) ruling the same cities that exist today in a world where electricity has been blocked from working. Of course, in the case of the Yukons, they began as a survivalist civilization, but with a very large overarching mission and a willingness to accept some outsiders—so long as they are white, English-speaking, and willing to conform to their puritan morality and stratified culture.

Seveneves by Stephenson has a similarly broad scope or apocalypse survival. In that novel, the Earth is going to be rendered uninhabitable by falling debris after the moon suddenly explodes, and it covers an international effort to save humanity by launching as many people into space as possible. Unlike other visions of the apocalypse, this international effort does not end up being divided by race or national origin, although fractures later form, and civilization largely ends up being driven by top-down plans for its continued survival.

Non-fiction plans for surviving serious apocalyptic disasters with any degree of plausibility generally focus on top-down planning as well. Feeding Everyone No Matter What, a favorite of mine, advocates for major government efforts to convert chemical factories to produce food, cut down forests to grow mushrooms, and generally expects a high level of intervention. Part of this is because these plans are written for governments, instead of for ordinary people.

But I think that, for the ordinary person, these ideas lack an inherent appeal. People want to be (and arguably always are) the protagonists of their own stories, and do not want to give up control. In Ragnar Benson’s explanation of why you should not become a refugee, he describes them as people with “no control over their destinies”. In a lot of ways, the fantasy of apocalyptic survival is the ultimate individualist fantasy, with the survivalist becoming a liberated Ubermensch who is freed from societal conventions and government, becoming superior to others by the simple fact of having survived what killed civilization.

It is also difficult to sit down, and say to yourself, “a nuclear war may happen tomorrow, and if it does, I will die.” There is an inherent desire to take control of one’s destiny and survive, although I have spoken to several people who have told me that without the comforts of modern civilization they would prefer to commit suicide than to continue to live in a world where they cannot access electricity, running water, and the internet. This is also part of the survivalist desire—if one looks at survivalist bunkers, many will include bowling alleys, movie theaters, video games, and pool tables. People want to keep their creature comforts, and that is one advantage of the apocalyptic shelter. If you are living in the mansion from Mountainhead or one of the very real tech billionaire shelters in New Zealand, you can expect to have your needs catered to in a similar fashion to the pre-apocalyptic world, including live-in servants and all the other perks of status. Stephen Baxter’s Flood, which I have discussed before, showcases this as well, with the billionaire Nathan Lammockson continuing to have personal servants aboard his survivalist ship.

One could argue that the modest luxury of a Vivos shelter or a backyard bunker is a desire to hold onto some sort of upper-middle-class lifestyle in the event of the end of the world, where you can drink moderately nice alcohol, sleep with a roof over your head on a bed with nice sheets, and not have to worry too much about violence or medical issues or where your next meal will come from.

In the face of an apocalypse, some authors would suggest a polite and considered acceptance of one’s demise and the extinction of humanity. The movie Don’t Look Up has the protagonists sitting around a table, holding hands, and savoring their last moments together as a world-ending comet approaches. To contrast, billionaires flee into space, and likely are doomed themselves. The video game SOMA has nearly all of humanity being killed by another object from outer space, and the survivors often commit suicide and/or retreat into a temporary virtual paradise. The game presents the possibility of survival as perhaps worse than a brief time living the good life before the end.

In a lot of ways, the possibility of the apocalypse presents us with the inevitability of our own, personal deaths. In truth, civilization is doomed, because eventually there will be no more usable energy in the universe, and then it will be over. Nothing lasts forever even without running out of the basic resources for survival. The basic attribute of life is that it will end.

Being a survivalist, then, is saying that one will struggle to survive. When, in Don’t Look Up, the protagonists accept the death of civilization and savor one last moment of true, positive joy, they are also accepting their own deaths, like a person who accepts that they will die and resolves to savor the positive parts of life, even if they are temporary. A survivalist is like the tech billionaire Bryan Johnson or other radical-life-extension believers, fighting against death that is probably inevitable.

And we have to recognize that, unless we are actively suicidal, we have that survivalist element in ourselves. The desire to survive is how we can extend our experience of the world, and most would agree that it is better to be alive than to be dead, even though life will inevitably end.

Bringing that back around to science fiction, I feel like there is something inherently relatable in survivalist, apocalyptic science fiction. We want to survive the apocalypse. But, if we do not fall in the same cultural vein as the survivalist science fiction authors of the past, we will not relate nearly as much to the survivalists of those stories. I am interested in seeing a newer wave of apocalyptic survival fiction, that takes a more positive perspective towards rebuilding after a disaster.

To some extent, I think that Seveneves fits that mold, where society ends up being imperfect but relatively pleasant to live in, after the long period of reconstruction is completed. I also feel like a lot of post-apocalyptic Solarpunk works fit this mold vaguely, although I have not read much in that particular genre. I think that something like The Ministry for the Future is horrible in the opposite direction as shoving people away from your liferaft—it’s about an overarching conspiracy working to harm many people against their will, for the good of humanity. A necessary sacrifice? Maybe, but probably not a more positive or less inhumane vision of apocalyptic survival.

Somewhere out there, I hope, there is a story that can balance realism, humanism, and empathy in surviving the end of the world.

Leave a comment