I recently read Michael Z. Williamson’s The Weapon, which I discovered after finishing is actually the second book in a series of libertarian military science fiction stories. It had some very interesting elements but was overall fairly typical for that genre, and one thing that the author discussed was the economics of the world that he depicted.

In The Weapon, the relatively small and unpopulated world of Freehold is able to overcome the forces of the much larger United Nations, because of a variety of factors. Freehold is lean and mean, compared to the bloated and decadent UN, they are willing to take cheap shots, they plan ahead, they have superior special forces, and they have superior technology.

In a lot of ways, this is a pretty common narrative which has been discussed in detail. The blog A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry has a pretty detailed breakdown of what they call “The Fremen Mirage”, where it is often believed that barbarian peoples on the edges of society enjoy natural superiority in military pursuits for many of the same reasons that Williamson’s libertarian space colonists do: a lack of decadence, viciousness, and superior individual soldiers. The author of ACOUP has a pretty good argument for why this isn’t the case. Even “decadent” societies can be vicious and produce good soldiers, and usually they produce more of them with more specializations and skills and money for training.

But in my mind, The Weapon is illustrative of the larger phenomenon of author fiat. The real reason why Freehold defeats the UN in The Weapon is because doing so reflects Williamson’s beliefs about the world. This is fairly intuitive, but a lot of the literary criticism I’ve read seems to miss this. I have read lots of scholarly essays where works “prove” or “show” something by depicting it on the page, but literature is not real life. It may take on elements of hyperreality, where it feels more real than real life, but that does not mean that it actually is more real than real life.

It might be true that Freehold would win the war with the UN if the events of that novel were to play out in real life, but the book is incapable of proving it either way. Instead, it may feel true to certain readers, and not to others.

For a very different example, my favorite book right now is Fitzpatrick’s War, by Theodore Judson. It’s set in a dystopian future, where a radical offshoot of North American culture militarily dominates a world without electricity using advanced technology. This premise, to me, does not feel true, but it feels plausible enough to forgive it. What the book is actually about, however, is the protagonist, Robert Bruce, and his relationships with the people around him, especially with the Lord Fitzpatrick, Fitzpatrick’s group of advisors and friends (which Bruce finds himself involved in), and his wife.

None of these interactions are real, because they did not happen between real people. But, to me, they feel incredibly real. Bruce forms a deep and lasting friendship with one of Fitzpatrick’s advisors, because he shows the man kindness when he is expected to be a bodyguard only and is treated cruelly by everyone. Bruce and his wife have an equitable and loving relationship in a world where women are supposed to always be subservient to their husbands, and the fictional editor of the book finds their simple romantic gestures (like dancing, holding hands, and kissing) to be incredibly obscene and shocking. And Fitzpatrick himself alienates Bruce by asking him to do cruel things to help build an empire.

To me, Fitzpatrick’s War feels incredibly true, because I believe in those relationships, and this is a somewhat fundamental quality of any good writing. The relationships have to feel real, the characters have to feel real, and the way that these things shape the story and their interaction have to feel real as well.

But in science fiction, there is more than just characters. Speculative fiction relies very heavily on setting, worldbuilding, and technical details, and that can change a lot of how the stories are perceived. In the case of Fitzpatrick’s War, there is a lot about the setting that doesn’t feel plausible. A secret society was able to build a set of satellites that shut down all electrical devices in the world, leading to a steampunk dystopia. Does this make sense? Maybe, but I suspect not. Of course, the characters and story are much more important than the setting to the way that the story feels, but they can still be important.

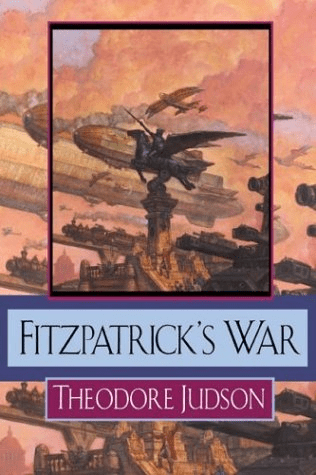

For example, when Larry Niven wrote his famous book Ringworld, he believed that the titular structure would be stable. Later, according to fable, he was sent a lot of fan mail explaining that this could not be the case, and apparently some MIT students even chanted “the Ringworld is unstable” at him. So he wrote a sequel, where he addressed many of these technical issues.

Ringworld is not like Fitzpatrick’s War. It is, fundamentally, about the novel ideas that it explores, in a universe where people can be bred to be luckier, teleportation has brought Earth close together, and enigmatic aliens send people on quests to primitive worlds. There are conflicts, but they are driven a lot more by the circumstances that the protagonists inhabit. In my mind, Ringworld is a worse novel than Fitzpatrick’s War, but it far greater cultural importance. It also relies entirely on the author’s authority with regard to the setting, which is why Niven felt compelled to write a sequel. A novel that is all about ideas has to have strong ideas.

It is also interesting to consider how this shapes movies. Movies exist in a position where they need more fiat, but may also exercise it less.

If you’ve ever watched a stage play, you’ll know that there’s always a bit of separation between what you’re literally seeing in front of you and the things that are supposed to be happening. The actors walk in front of a curtain, their costumes are not especially realistic, there’s an intermission and pauses. So the audience relies on many of the same resources that tell us what’s going on in a book. The names and natures of characters are told to us, or shown to us through actions instead of through how they look. If we know one of the actors, we have to intentionally hold that separation, and tell ourselves that they are the characters they are listed as in the playbill.

Movies, on the other hand, don’t have to deal with a lot of these things. They are often very high budget, and so they can have photorealistic costumes. If we do not recognize the actors, it is very easy to believe that they are the people they claim to be. The way that films are edited also allows the movie makers to hold our attention more involuntarily. Instead of curtains dropping, breaks, and intermissions, scenes cut to each other immediately and instantly. Actors never get tired in a well-produced movie, and we can see many back-to-back scenes of different things happening. This reduces the amount of credibility the creators have to build, or, perhaps, it is a way for them to establish credibility very forcefully. They can show us things happening, and we see them, and that makes them credible.

But for science fiction, the medium of film has its own challenges. The fact that you get to show things means that you have to show things, and then you end up with stuff like your audience members using the pixels on their screens to measure your spacecraft and tell you that it’s impossible.

In 2019, Brad Pitt starred in the movie Ad Astra, where he plays an astronaut who is traveling into the outer solar system to find his father, who is believed to be behind enormous technological disasters affecting Earth and the other planets.

The movie is aesthetically very impressive, and it feels plausible in that regard. The moon is presented first as an airport, and then as a piratical warzone. On the way to Mars, they visit a research station, and then Mars itself feels like a desolate Antarctic outpost, with many people working very hard to survive in a desolate place. Then, in the outer system, things feel more reminiscent of the ISS or other real-world space stations. All of these aesthetics are strong and feel real to us, because they are. Brad Pitt’s character’s complex relationship with his father, who has gone insane after failing to find intelligent life in outer space, is also plausible, and the movie has themes of isolation that are woven throughout it. All of these things make it very competent in the conventional sense, and it was relatively well received by critics.

Of course, if you ask space nerds about the movie, they have a very different opinion. Much of the movie makes no technical sense at all. The main character’s father sends signals that destroy electronics across the solar system from Neptune, somehow. The travel times are too short, the rockets are too small, and there’s no way that they could have visited a research base. It’s been mocked on podcasts and by science fiction fans everywhere, and that doesn’t make it a bad movie. It just means that the film lost its technical credibility, and for those people, that was the important thing.

There is a piece of science fiction writing advice I’ve seen, which says that you should never use numbers, because you will always have fans that are more dedicated to scientific accuracy, who have more specialized knowledge, and who are smarter than you. This is true.

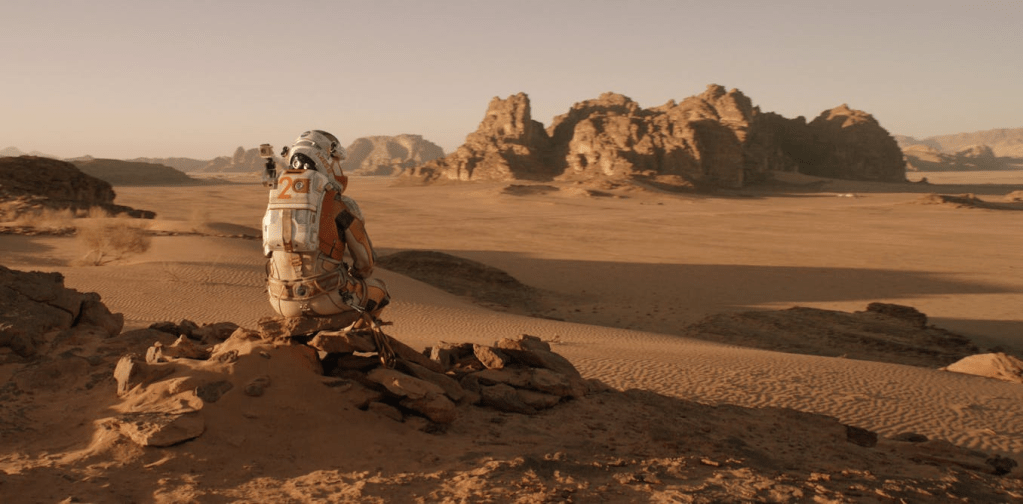

But I do also believe that showing specific, non-speculative knowledge could be a good substitute to build credibility with the audience. Andy Weir’s The Martian does a good job of this, where the details of the Mars mission are laid out in some detail, but rarely with any numbers.

The details of Mars’s surface, however, are described lovingly and sometimes even numerically. We get specific information about the length of the day, the weather, the chemicals available on the surface, because these things are things that Weir could find in scientific literature and include in his book. It’s a great way to build credibility, and the fans that know more than you will nod at your technical knowledge. They might believe that they want more details, and ask questions like “what exactly is the size of the Mars Ascent Vehicle?” or “exactly how much power does everything use?” but in truth, the answers to those questions will make them enjoy the work less.

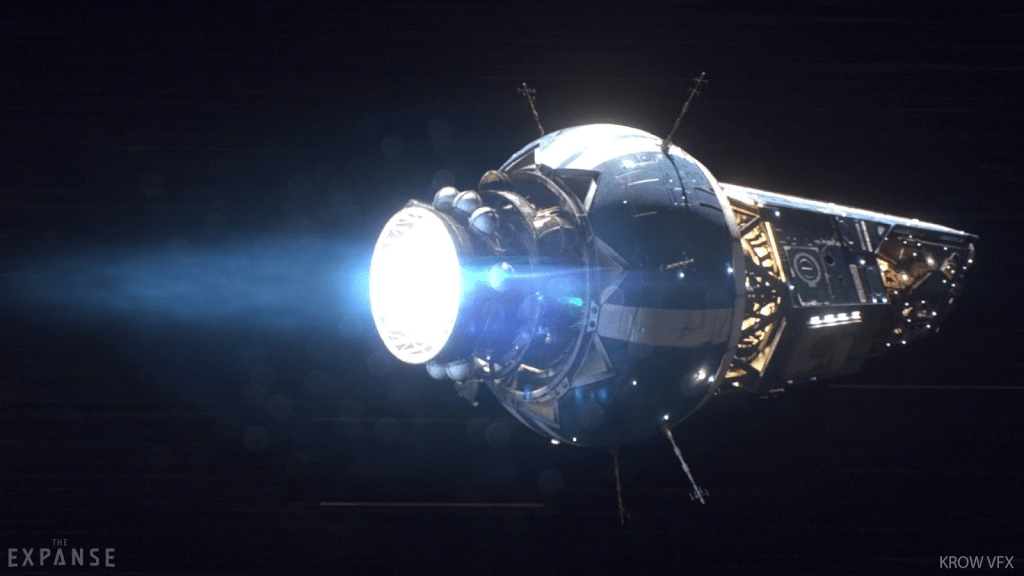

Another good example of this phenomenon is in the Expanse series. The books are pretty good about respecting science early on, except in the depiction of the protomolecule zombie plague/wormhole building nanomachines which are pretty much magic. But the authors chose to take liberties with the depictions of space travel by including an unrealistically, impossibly good space drive which allows ships to accelerate at 1g.

The Expanse was received well by many science fiction fans, and even got a TV show adaptation (which is also quite good), but not everyone feels the same way. I have a degree in aerospace engineering, and a lot of my friends are in the field or have similar backgrounds, and just about everyone in that field will say something like “it’s cool, but the way their spaceships work makes no sense!” People who know about nuclear and rocketry technology have tons to say about the series’s technical realism, and their consensus is generally that it doesn’t make much sense at all, if you think about it for a while.

Of course, many of these people are able to look past the implausible technical aspects to focus on the rest of it, and I think that a lot of it is wishful thinking. People want to live in a future with a colonized solar system, and The Expanse makes that feel real and beautiful, even if the world is divided, full of conflict, and downright dystopian in some places. Like my experience with Fitzpatrick’s War, the author’s were able to build up enough credibility in other areas of storytelling to overcome a technically-minded audience’s natural resistance to a story with some technical mistakes.

I believe that this is a fundamental weakness of the very old-school approach used by Niven. Stories that only work because of their interesting ideas are only as strong as those ideas, but stories that are based on timeless, inherently-compelling aspects (like characters, aesthetics, and interpersonal connections) can be much stronger than their ideas.

Of course, as a science fiction writer, it is also important to have strong ideas. But for those of us who, like me, are unlikely to have genre-altering ideas about the world, the future, and technology, it may be wise to study first the human heart.

Leave a comment